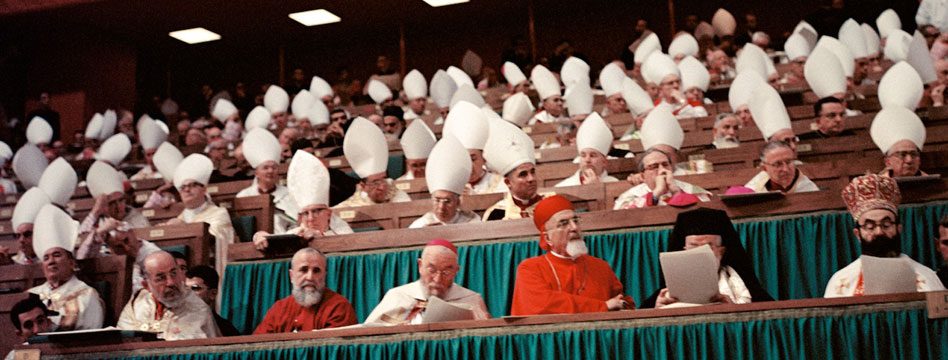

Two moments of reform and renewal in the Church

Ordinarily, the Council of Trent and Vatican II are contrasted as two entirely different species, genera or even universes. Most priests, during their formation, become familiar with some of the canons of Trent and are aware of its succinct statements defining Catholic doctrine against the Protestants. They tend to study the texts of Vatican II in greater detail and will take up a position of greater or lesser enthusiasm for its celebrated opening of the windows, aggiornamento and reform. They may be positive about all this, or increasingly today, more critical of some of the ways in which Vatican II has been used to promote a hermeneutic of rupture – something we will consider in the next paper.

My ambitious project today is to compare rather than to contrast the two councils. It is easy enough to contrast them: to take an obvious example, Trent made doctrinal definitions in the face of Protestantism whereas Vatican II promulgated the Decree on Ecumenism. However, even here we should remember that the first purpose of Trent was reconciliation and ecumenism. It is surprising to learn of the extent to which at least the early sessions of Trent were aimed at bringing about peace within Christendom.

My intention is to show on the one hand that Trent had a concern for issues that remained part of Catholic activity into our own time, and that Vatican II was far from being a non-doctrinal council, albeit there was no intention to make new definitions of doctrine. I will focus on the renewal of the priesthood desired by both councils which is of particular relevance to us at this conference.

Background to Trent

The 5th Lateran Council met from 1512 to 1517 and comprised five sessions, primarily asserting the rights of the Church and the dignity of Bishops, as well as calling for a war against the Turks. Martin Luther published his 95 theses just seven months after its close, and himself called for a general council, though with the intent of it being in a conciliarist spirit. The Protestants later called for a German national council.

The Emperor Charles V was keen for there to be a Council whereas King Francis I of France opposed it. During the 1530s there was a series of disputes, mainly political in nature which delayed the calling of a Council, though some Cardinals were also opposed. Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who had been a strong supporter of a Council, was elected Pope in 1534 and immediately announced his intention of calling one. After further delaying tactics on the part of Francis I, and indeed Henry VIII, difficulties over the venue with Mantua and Vicenza both proving problematic, and the opposition of German protestants, Paul III finally got the council off the ground in December of 1545. There were three periods during which the Council met. The first was from 1545 to 1547 under Paul III, and the second from 1551-1552 under Julius III. Julius was succeeded by Marcellus II who had a stroke and died 22 days after his election. The next pope Paul IV (Carafa) was not interested in continuing the council because he saw no point in attempting to reconcile the protestants and the council did not re-start until 1559 under Pius IV. During this third period, the work of the council was helped greatly by the presence of Cardinal Charles Borromeo. By 1563, the fathers and everyone else were keen to conclude the work.

Both Trent and Vatican II were called at a time of religious, cultural and social upheaval. In the sixteenth century, the reformers at their purest were determined to rid the Church of corruption, and to bring about a new flowering of the spiritual life among the laity. We know of course that this intention was diverted into the denial of the priesthood and the sacrifice of the Mass, and the loss of many devotions that were loved by the faithful. However, there were elements of the devotio moderna which can be discerned in the reforming movement and which were shared by some of the Fathers of the Council.

Vatican II, called in the wake of the second World War, was also concerned with a significant turmoil in society. As we have seen, Blessed John XXIII was optimistic about the contribution of the Church to the renewal of human culture and to the promotion of every human good. Sadly there was a reluctance to address the significant scourge of Marxism, and in the early sixties, secularism had not matured to the point that we are familiar with today. However there was an overwhelming desire to promote peace in the world, unity among Christians, and the greater flowering of the Christian life in the Catholic Church, a life which was so strong in the years immediately preceding the Council.

In this respect, an important comparison between Trent and Vatican II can be made by way of contrast to a popular assumption. The classic Whig history approach to the reformation saw the Church as weak and on its knees before Trent, desperately in need of the Protestant reformation. Eamon Duffy and other historians have effectively overturned this reading of history by showing evidence of the life of the Church before the reformation, especially in the life and activity of ordinary parishes.{{1}} With regard to the 20th century, many make the assumption that the Church was ossified and moribund before Vatican II and crying out for change and new life. A recent online debate in England has shown statistical evidence which undermines this view of things, and any honest appraisal of the normal life of parishes in the first half of the twentieth century would conclude that the Church was in great health, not least in the contribution of the laity to the work of the Church though apostolic groups, catechesis and charitable work.

Fergus Kerr, a Dominican scholar generally not reckoned as particularly conservative or traditional, recently wrote a book on twentieth century theologians.{{2}} In the chapter on Hans Kung, far from an account of how bad things were before the Council and how much the Church needed to change, we find, perhaps surprisingly, that in 1961, Kung referred in very positive terms to the life of the Church at that time.{{3}} It is amusing to read that as a young student, Kung went joyfully in the cassock and fascia of the German College to attend what he considered the inspiring occasion of the infallible papal definition of the Assumption.

Surely though, the popular assumption would be, the Council of Trent was concerned with doctrine whereas Vatican II was a pastoral council? Here again, history teaches us a more nuanced perspective. It is true that Trent formulated new definitions of the faith of the Church in response to the Protestants, more terse and succinct as it became obvious that attempts at unity were doomed to failure. However the bulk of the text of the documents of Trent is found in the lesser known decrees De Reformatione, giving detailed prescriptions for the pastoral reform of the Church in matters of how Bishops should behave, how priests should be educated, and how the spiritual life of the faithful should be safeguarded.

In the case of Vatican II, let us recall again the words of Blessed John XXIII that the greatest concern of the Council should be

that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be guarded and taught more efficaciously.{{4}}

And in fact, the texts of Vatican II include the re-statement of doctrinal definitions, for example on the knowability of God from the natural light of human reason, and on the infallibility of the Roman Pontiff.

Both Councils were concerned with both pastoral reform and the affirmation of doctrine. In the case of Trent, we tend to forget the pastoral concern, and in the case of Vatican II, we tend to forget the doctrinal statements.

Justification and the Church

The Decree on Justification, of session 6 of the Council of Trent, is the masterpiece of the Council. It took seriously and answered methodically the heresy of Luther on the question and provided, together with the earlier decree on original sin, a blueprint for the subsequent treatment of grace in Catholic theology. It does not require any artificial reconciliation to see Vatican II’s emphasis on the sacrament of Baptism, and on our insertion into the paschal mystery, as a development of the teaching of Trent and a continuation in the same line of witness to the gospel. For example, in chapter 3 of the Decree on Justification, we read of how it is only those to whom the merits of Christ’s passion is communicated (by being born again in Christ) who are justified. The Decree says:

in that new birth, there is bestowed upon them, through the merit of His passion, the grace whereby they are made just. For this benefit the apostle exhorts us evermore to give thanks to the Father, who has made us worthy to be partakers of the lot of the saints in light, and has delivered us from the power of darkness, and has translated us into the Kingdom of the Son of his love, in whom we have redemption, and remission of sins.

In Lumen Gentium, the Fathers consider the same biblical text in relation to the Church:

The baptised, by regeneration and the anointing of the Holy Spirit, are consecrated as a spiritual house and a holy priesthood, in order that through all those works which are those of the Christian man they may offer spiritual sacrifices and proclaim the power of Him who has called them out of darkness into His marvellous light.

Trent focussed on justification in response to the immediate need of the time. Vatican II focussed on the effect of this justification, namely our becoming part of the Church, and the implications for Christian life which follow from our membership of the body of Christ.

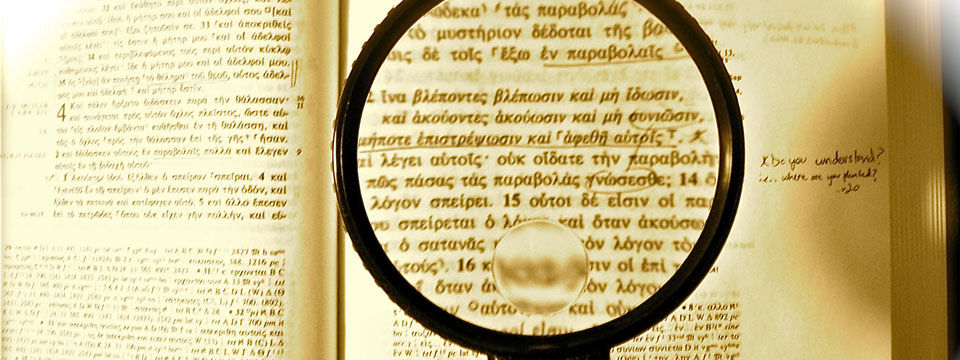

The Scriptures

In the fourth session (1546) Trent listed the canonical books of Holy Scripture. In doing so, the Council Fathers said:

Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, first promulgated with His own mouth, and then commanded to be preached by His Apostles to every creature, as the fountain of all, both saving truth, and moral discipline; and seeing clearly that this truth and discipline are contained in the written books, and the unwritten traditions which, received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the Apostles themselves, the Holy Spirit dictating, have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand.

In the Constitution on Divine Revelation, Vatican II teaches:

Hence there exists a close connection and communication between sacred tradition and Sacred Scripture. For both of them, flowing from the same divine wellspring, in a certain way merge into a unity and tend toward the same end. For Sacred Scripture is the word of God inasmuch as it is consigned to writing under the inspiration of the divine Spirit, while sacred tradition takes the word of God entrusted by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit to the Apostles, and hands it on to their successors in its full purity, so that led by the light of the Spirit of truth, they may in proclaiming it preserve this word of God faithfully, explain it, and make it more widely known. Consequently it is not from Sacred Scripture alone that the Church draws her certainty about everything which has been revealed. Therefore both sacred tradition and Sacred Scripture are to be accepted and venerated with the same sense of loyalty and reverence.{{5}}

It might be irreverent to argue that there is no difference here between Trent and Vatican II except that Vatican II is more verbose. The point is, surely, that on a matter which some theologians after the Council argued was a decisive break with the past in speaking of “the same divine wellspring” and of “one sacred deposit” for scripture and tradition, is in fact in exact concordance with the teaching of Trent. Trent had the specific task of defining the canon of scriptures and Vatican II explored the question of revelation in greater depth, but, if we wish to use the vague emotive language so often used in relation to the two Councils, Trent was more forward-looking than is usually realised, and Vatican II is more traditional.

It would be an easy enough task to collect many other examples of similarities between the texts of both councils, and quite fun, but I hope that the point has been made sufficiently.

Catechisms

The Tridentine Decretum de Reformatione of 11 November 1563 encouraged bishops and priests to catechise the people on the occasion of the administration of the sacraments. Part of this work, completed after the council, was the preparation and publication of a Catechism to enable pastors to preach properly. As we shall see, the initial reform of the education set what we might consider a low standard for the level of knowledge required for ordination, though it was a significant improvement at the time. The priest was particularly required to be able to instruct people for the sacraments. The Tridentine Catechism was prepared with this in mind and was therefore addressed to priests who had the care of souls.

For the Year of Faith, Pope Benedict recalled both the 50th anniversary of the opening of the second Vatican Council and the 20th anniversary of the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, referring to it as “an authentic fruit of the Council.”{{6}} In the introduction to his letter Fidei Depositum on the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Blessed John Paul II gave us yet another affirmation of the purpose of Vatican II as envisaged by Blessed John XXIII:

The principal task entrusted to the Council by Pope John XXIII was to guard and present better the precious deposit of Christian doctrine in order to make it more accessible to the Christian faithful and to all people of good will.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church had a different immediate focus from the Catechism of the Council of Trent in that it was intended to serve as a point of reference for catechisms or compendiums that were prepared for various regions. However, its overall purpose was, like the Tridentine Catechism, to renew the life of the whole Church, and its structure was the same, following the Creed the Sacraments, the Commandments and Prayer, though giving an expanded treatment with reference especially to the scriptures and to the Liturgy.

Liturgy

One aspect of Vatican II that has not been widely implemented is to give the study of the Liturgy a more important place in theological studies. Sacrosanctum Concilium (n.16) urged that the study of the Liturgy should be among the compulsory and major courses in seminaries, and to rank among the principal courses in theological faculties. In many places, Liturgy is ranked among the more minor, specialised, additional courses, while others continue to treat the course simply as a study of the ceremonies and practical instruction in celebrating them.

Sacrosanctum Concilium went further:

Moreover, other professors, while striving to expound the mystery of Christ and the history of salvation from the angle proper to each of their own subjects, must nevertheless do so in a way which will clearly bring out the connection between their subjects and the liturgy.

I do not think it would be unfair to say that this instruction remains largely unimplemented.

Both the Council of Trent and Vatican II sought to reform the Liturgy and to restore it to its pristine form. In the Apostolic Constitution Quo Primum of 1570, by which the standardised Roman Missal was promulgated, Pope Saint Pius V said:

From the very first, upon Our elevation to the chief Apostleship, We gladly turned our mind and energies and directed all our thoughts to those matters which concerned the preservation of a pure liturgy, and We strove with God’s help, by every means in our power, to accomplish this purpose.

He entrusted the work to “learned men of our selection” and describes the result of their labours:

They very carefully collated all their work with the ancient codices in Our Vatican Library and with reliable, preserved or emended codices from elsewhere. Besides this, these men consulted the works of ancient and approved authors concerning the same sacred rites; and thus they have restored the Missal itself to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers.

We might want to argue about the extent to which the work succeeded, whether there remained elements in the Roman Missal of 1570 which were not genuinely part of the original form and rite of the Fathers, but it is clear that the intention of St Pius V was not to create a new Missal but to standardise that in existing use.

The second Vatican Council did have various other intentions in its reform of the Liturgy. It expressed a desire for clearer expression, intelligibility and active participation.{{7}} These concerns are obviously different from those of St Pius V (although the Council of Trent did discuss the possibility of introducing the vernacular into the liturgy) however, the desire for restoration and fidelity to the Fathers is also present as Pope Paul made explicit in 1969 in his Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum.

The question of the relationship between the Missal of Paul VI and the Missal of St Pius V, remains controversial and it is not my principal concern to discuss it here. Both Trent and Vatican II desired to restore the Liturgy to that of the Fathers. Both have been criticised for failing to do so and for making textual and historical errors in their efforts. Perhaps we may see a salutary admonition in the words of Sacrosanctum Concilium itself:

Finally, there must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them.{{8}}

Reform of the Priesthood

One of the major tasks of the Council of Trent was the reform of the clergy. The first problem was that there were too many priests and that, as Duval notes, many of them lived “in material and moral destitution.”{{9}}

Alongside the many ignorant and incompetent priests were a small number who inspired others through their good example by leading holy lives and dedicating themselves to observing the sacred canons. The ideals of the priesthood exemplified by these men were set out in the various manuals for priests that began to appear with the invention of printing. As well as the sacramental ministry, these reformers within the Church stressed the importance of preaching. Duval notes that when the Romans saw the first Theatines in 1525 preaching in cassock and surplice rather than the habits of the religious who had until then been the only preachers that they had experienced, their response was to cry Miracolo!

The moral corruption of the clergy was a major factor in popularising the Lutheran opposition to the Church. The reformation of the life of the clergy was correspondingly one of the most important concerns of the Council of Trent. In chapter 14 of the Decree of Reform of the 23rd Session (1563), it was required that for priesthood, the priest ought to know all that was necessary for salvation and for the administration of the sacraments. This was something of a compromise. A draft stipulation, that nobody should be ordained Deacon unless he were deemed fit to preach, was so controversial that it was removed. A further question was that of age. Some Spanish bishops wanted the minimum age for ordination to the priesthood to be fixed at 30. Part of the reasoning for this was the difficulty for young people of observing chastity. The solution adopted was not the late age but the establishment of seminaries for the training of priests.

Chapter 18 of the Decree on Reform gave instructions for the setting-up of seminaries in every diocese, or joint seminaries within a province if resources were not adequate in individual dioceses. It is a breathtaking irony of history that the Decree’s provision for seminaries was based on the Decree for England, drawn up by Cardinal Pole and agreed by the Synod of London in 1556 during the reign of Queen Mary. In just a few years, it would be a capital offence to train for the priesthood, and there would be no English Seminary founded on the Tridentine model until the foundation of St John’s Seminary, Wonersh in the late 19th century.

Concerning the institution of seminaries, Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino wrote:

Above all the institution of seminaries was approved, many being heard to say that if no other good were to come from the present council, this alone would compensate for all the labours and all the inconveniences, as the one instrument which was looked upon as effective in restoring the lost discipline.{{10}}

(On the question of celibacy, the Council did not yield to the considerable pressure of the German imperial representatives to relax the rule in order to end the scandal of concubinage. In fact, the Council did not deal at all with the theological or canonical questions regarding priestly celibacy.)

Paul VI on Tridentine Seminaries

On the feast of St Charles Borromeo, 4 December, in 1963, Pope Paul VI gave an address on the 400th anniversary of the Council of Trent’s call for the establishment of seminaries. In it, he spoke particularly to seminarians to encourage them. He said they should have “a big eye and a clear heart” and imitate Christ with heroism. He said he was confident to give this advice because the Church had the means to help them. He added:

But today, the Church has made herself capable and will be even more so in the future, of exercising her sublime mission as the educator of future priests, because the Church has instituted her seminaries for this purpose. The seminary is the school of inner silence, in which speaks the mysterious voice of God. It is the training unit for training in the difficult virtues. It is the house where Christ, the Master, lives.

We all know what actually happened in the aftermath of Vatican II, but if we want, during the Year of Faith, to be faithful to the vision of Pope Paul VI and of the Council itself, it is necessary to return to this understanding of the seminary, as indeed being done gradually in many places.

Optatam Totius

Vatican II’s Decree on Priestly Training began with a statement that shows a remarkable similarity to the programme of Trent:

Animated by the spirit of Christ, this sacred synod is fully aware that the desired renewal of the whole Church depends to a great extent on the ministry of its priests.

It went on to speak of basic regulations “which long use has shown to be sound” and of new elements which correspond to “the changed conditions of our times.” The Decree bluntly stated that “Major seminaries are necessary for priestly formation” (n.4) recognising the now firmly embedded principle of the Council of Trent’s reform. With regard to the worthiness of candidates, Trent was especially concerned to root out corruption in the matter of benefices and non-residence, as well as nepotism and preference for the rich.

While Vatican II did not need to concern itself with these particular abuses, it nevertheless enjoined firmness in selecting suitable candidates for Holy Orders:

In the entire process of selecting and testing students, however, a due firmness is to be adopted, even if a deplorable lack of priests should exist, since God will not allow His Church to want for ministers if those who are worthy are promoted and those not qualified are, at an early date, guided in a fatherly way to undertake other tasks.{{11}}

With regard to the required training, Vatican II was rather stronger than Trent in many areas. The general corruption of the clergy which the Tridentine decrees addressed, had largely been overcome by the steady implementation of those decrees and the standard expected of students had become much higher. Nevertheless, both councils insisted on the importance of piety and knowledge on the part of candidates for Holy Orders. With regard to celibacy, the censures and penalties attached to concubinage at Trent gave way to a more positive exhortation to chastity at Vatican II. One could say that the problem of sexual misconduct was greater before the council in the case of Trent but greater after the council in the case of Vatican II.

Optatam Totius speaks of discipline in one of those paragraphs in which it is easy to detect two opposing viewpoints. On the one hand it speaks of the importance of discipline for promoting community life and charity and as a means of self-mastery. On the other hand, it urges that seminary discipline should be maintained so that the students accept the authority of superiors from their own internal conviction. Some of us experienced this approach in practice: clearly written rules were rare, but it became necessary to discern the unwritten rules, the breach of which would be taken to indicate rigidity, a lack of openness or some other psychological defect.

Priestly piety

In addition to providing for the training of priests, the Council of Trent fostered the spiritual life of priests. One of the fruits of the Council and especially of the gradual establishment of seminaries was that over a period of time the expectation grew that the priest would live a holy life. This reform certainly did not happen overnight but may legitimately be considered one of the long-term fruits of Trent.

By the time of Vatican II, the establishment of a basic rule of life was taken for granted in seminaries, as a preparation for the mission. Naturally there were exceptions but in general it was fairly clear that the priest was expected to pray the office, celebrate Mass daily if possible, spend some time in meditation, say the Rosary, and set some time aside each day for spiritual reading. The Decree on the Ministry and Life of Vatican II assumes this priestly spirituality and relates it to the vocation of baptism:

In the fulfilment of their ministry with fidelity to the daily colloquy with Christ, a visit to and veneration of the Most Holy Eucharist, spiritual retreats and spiritual direction are of great worth. In many ways, but especially through mental prayer and the vocal prayers which they freely choose, priests seek and fervently pray that God will grant them the spirit of true adoration whereby they themselves, along with the people committed to them, may intimately unite themselves with Christ the Mediator of the New Testament, and so as adopted children of God may be able to call out “Abba, Father.” (Rom 8:15){{12}}

In his letters to priests on Maundy Thursday and his allocutions, especially related to the example of St John Vianney, Blessed John Paul reaffirmed this essential continuity between Trent and Vatican II regarding the spiritual life of priests.

Reverence for both councils

As I said at the beginning, the project of comparing rather than contrasting Trent and Vatican II is an ambitious one but it is not without its fruits. There is much to be gained by being open to learning from Trent and Vatican II seen as part of the long-term process of reform and renewal in the continuity of the one subject Church.

Fifty years one, there is still what one might call a reverence for Vatican II. The papal magisterium and informal teaching of Blessed John Paul and Pope Benedict contained many references to the Council. Perhaps the relative lack of such references in the teaching of Pope Francis indicates that there is now a certain maturity in its acceptance. One of the purposes of this paper is to affirm that this reverence for Vatican II is not in any way lessened by a reverence for the Council of Trent. With far fewer resources, that council also brought about a great improvement in the life of the Church, and especially in the life of the clergy, from which we still benefit today, though often without acknowledging the achievement of Trent.

A shining example of the implementation of both the letter and the spirit of Trent is St Charles Borromeo. He was a participant in the later stages of the council, and it is said that he knew the decrees by heart. He was himself a part of the corrupt establishment of the day. He was tonsured at the age of twelve and his uncle, Julius Caesar Borromeo gave him the revenues of the Abbey of Sts Gratinian and Felin. St Charles made it clear that beyond the expenses necessary to prepare for the priesthood, these revenues would go to the poor. At the age of 22, he was made Cardinal by another uncle, Pope Pius IV, and Administrator of the Diocese of Milan, though he had not yet been ordained priest. He was finally ordained in 1563 and was made Bishop a year later.

His entry to Milan was greeted with enthusiasm, not least because it was unusual for such noble Bishops to visit their Dioceses. The joy turned to consternation when it became clear that he intended not only to be resident as Bishop but to implement the decrees of Trent which he did in the face of bitter opposition.

We do not lack examples today of inspiration in the reform of the Church. Blessed Charles de Foucauld, Blessed Jerzy Popielusko and St Josemaria Escriva show in different ways the turning of the Church to those of other faiths, the Church’s commitment to the transformation of society, and the apostolate of the laity. In the meantime, the ever-present and beloved figure of St John Vianney stands as an icon of continuity between Trent and Vatican II both in doctrine and piety.

[[1]]The most celebrated work is Duffy, E. The Stripping of the Altars. Yale University Press. 1992.[[1]]

[[2]]Kerr, F. Twentieth-Century Catholic Theologians: From Neoscholasticism to Nuptial Mysticism. Wiley-Blackwell. 2006.[[2]]

[[3]]For example, in his book The Council and Reunion. Sheed and Ward. London 1961 (originally published as Konzil und Wiedervereinigung. Herder. Freiburg im Bresgau. 1961).[[3]]

[[4]]Bl Pope John XXIII. Allocution at the Solemn Opening of the second Vatican Council, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. 11 October 1962. n.5.[[4]]

[[5]]Dei Verbum n.9.[[5]]

[[6]]Porta Fidei n.4.[[6]]

[[7]]Sacrosanctum Concilium n.21.[[7]]

[[8]]Sacrosanctum Concilium n.23 (Innovationes, demum, ne fiant nisi vera et certa utilitas Ecclesiae id exigat.).[[8]]

[[9]]Duval, A. “The Council of Trent and Holy Orders” in The Sacrament of Holy Orders. Aquin Press. London. 1957 pp219-258.[[9]]

[[10]]P. Sforza Pallavicino, Istoria del Concilio di Trento. A.M. Zaccaria (Roma, 1833) IV. 344.[[10]]

[[11]]Optatam Totius n.6.[[11]]

[[12]]Presbyterorum Ordinis n.18.[[12]]