Fr Tim Finigan was keynote speaker at the 2013 ACCC Conference. This is the first of four papers he presented at the conference. They were:

Understanding the dynamics involved in the Council

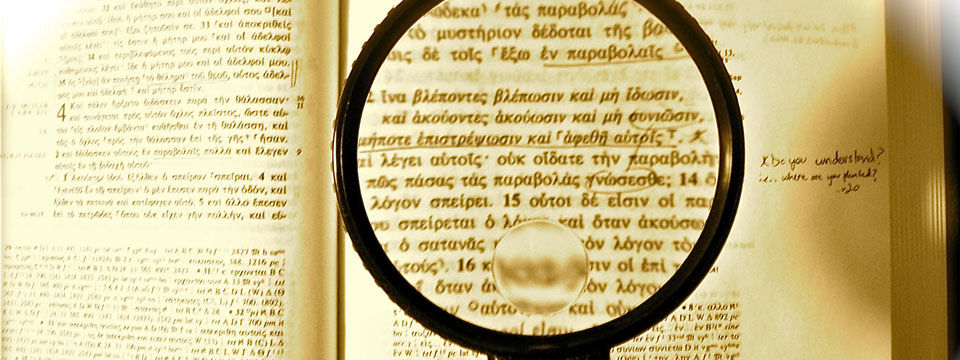

Pope Benedict asked us to celebrate a Year of Faith throughout the whole Church. He asked us particularly to look at the second Vatican Council, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, and the New Evangelisation. I will be focussing particularly on the second Vatican Council, first of all in this lecture on its background and history which I find fascinating in view of the way that many people characterise both today. In the second lecture, I will be comparing Vatican II and the Council of Trent. As one who has the task of setting exam questions, I deliberately set myself the task of comparing rather than contrasting, since I thought that would be more fruitful. Then in the third lecture, I will look at the concept of the hermeneutic of continuity or, put more simply, his encouragement to us to see the Council in the light of the tradition of the Church and her constant need for renewal and reform. I will try to apply this to some of the controversial texts of the Council. In all of this, I hope to keep focussed also on our task of evangelisation which we wish to renew during the Year of Faith. I do not wish simply to give my own opinion but to refer throughout to the primary sources: the texts of the Council and the various papal addresses, and formal documents, as well as some secondary sources. The primary texts of the Popes and of the Council documents are by far the most important. The opinions of others serve only to help us to understand the primary texts.What is a Council?

First of all we must remind ourselves what a Council is. (Another word often used in the early history of the Church is “synod.”) Throughout the history of the Church there have been many gatherings of Bishops and theologians locally nationally and internationally. Some of these councils have been of great importance and are studied in the history of the Church as landmarks, often clarifying particular points about Christian doctrine, liturgy and practice. Some of them are of little importance to us today except as evidence for the historian. (For example, Alexander of Hales, despairing of scriptural evidence for the Dominical institution of the sacrament of Confirmation held that the fathers of the Council of Meaux (convoked by Charles the Bald in 845) were inspired by the Holy Spirit to specify the matter and form of the sacrament.) As we know, Vatican II was not one of these lesser councils but an “Ecumenical Council” or a “General Council of the Church.” The Catholic Church recognises 21 Councils as General Councils of the Church. Essentially, a council is a General Council if it is a gathering of Bishops from around the world, under the authority of the Pope, to decide matters of faith, morals and discipline within the Church. The bishops do not go as representatives of the people, as would be the case, for example in the European Parliament or the United Nations. Although Councils involve voting, the idea is not to have a merely human democratic consensus, but to proclaim the teaching of Christ authoritatively and with divine assistance. Hence the first act of a Council is to invoke the Holy Spirit. Historically there have been Councils at which the Pope was represented by legates, or even Councils which have been subsequently approved by the Pope. In modern times, it would be unthinkable for a Council to be called except by the express and authoritative decision of the Pope. A Council does not have the authority to control or limit the power of the Pope (which is given to him by Christ) but it could complain to the Pope on some matter of the exercise of his ministry. The principal feature of a General Council is that it is at least in principle universal. That is what the term “ecumenical” indicates – the oikumene is the whole world and a General or Ecumenical Council calls together the Bishops of the whole world. In the past it was not always possible for all the Bishops to travel to a particular place but there had to be at least the principle of universality. So the second Vatican Council was an Ecumenical or General Council because it was called by Blessed John XIII formally and authoritatively, all the Catholic Bishops of the world were invited, and they gathered to consider the faith, Christian life, and the governance of the Church. Among the others of the 21 Councils that have happened in history, there were considerable differences in their importance and in their character. The first General Council of Nicea in 325 was a crucial and foundational battle on which depends all subsequent orthodox theology. No tract in theology would be the same if Jesus Christ were not truly God. Nicea, as we know, countered the heresy of Arius who said that Jesus Christ was less than God, like a ray from a light source or a kind of demi-god from the true God, something different from the Godhead of the Father. Hence we say in the Creed every Sunday at Mass the words set down by that Council that Jesus Christ is:God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father.After the Council of Nicea the Church was immediately split. For over fifty years, heretics and emperors argued with those who were orthodox. St Athanasius, the champion of the orthodox faith was exiled five times. For a Catholic living around the middle of the fourth century, it would have been reasonable to say that the Council had been a failure and that the true faith was doomed. Yet in God’s providence the teaching of the council remained a touchstone of orthodoxy on the divinity of Christ throughout history and to the present day. Cardinal Ratzinger wrote that:

Not every valid council in the history of the Church has been a fruitful one; in the last analysis, many of them have been a waste of time.{{1}}In a footnote, he gives an example:

In this connection, reference is repeatedly made, and with justification, to the Fifth Lateran Council which met from 1512 to 1517 without doing anything effective to prevent the crisis that was happening.We may therefore say that a council was indeed a failure in human terms. Lateran V did not teach heresy but neither did it do anything effective to meet the challenge of the split in the Western Church which we now know as the Reformation. On the other hand, the Council of Trent which met on and off from 1545 to 1563, was a remarkable success, despite many human factors which could have made it useless. In some ways it dealt timidly with the abuses which occasioned the reformation, but it set down definitions of doctrine which were of tremendous value, reformed the priesthood, and went a long way to beginning a lasting reform of the Church from which we still benefit. To take just one example, we now take it for granted that priests receive training before they are ordained. That was not the case before the reforms of Trent. In this historical perspective, a particular characteristic of Vatican II was that the Pope did not intend for it to make new definitions of doctrine, but to be a pastoral council. It was the most “Ecumenical” in the sense that modern means of travel made it possible for the Bishops of the world to gather. It was unlike many councils, in that it did not issue “anathemas” (formal condemnations of heresy), but it was like many councils, in that it was followed by a period of turmoil. We are still living through that turmoil which is why Pope Benedict has called for us, fifty years on, to take a fresh look at its teaching in the interests of genuine reform and renewal.

The history and context of the council

The Council began in 1962. That was 17 years after the end of the second world war. To put that in perspective, 50 years prior to that was 1912. For a young person today, the events of the 1960s are as remote as the first world war was to a child of the sixties. With hindsight, we can see that the Council took place during the prolonged aftermath of the second world war. Christians responded to that terrible war with a desire for peace, for brotherhood, and for unity. In England there was a prolonged period of austerity after the war; I remember the tin my mother had with ration cards, smog masks and a small bottle of smelling salts which we used to play with. That austerity was followed by a rapid growth in prosperity and relative liberty: the era which was heralded in 1957 by Harold MacMillan’s “You’ve never had it so good.” During the sixties, the sombre and stirring remembrance of heroism gave way to jokes about grandad’s war wounds, the celebration of the modern (I watched Croydon grow daily during my school years) and a desire for freedom from authority, rules and anything that smacked of the old order. To call someone a “square” was not an ironic joke as it is now, it was a genuine insult. Ordinary people felt the need to be “with it.” The Beatles, the Rolling Stones – and indeed Jimmy Savile – were icons of the new, free era which developed into the age of aquarius, glam rock, and generally “let it all hang out.” In the West, this was the cultural background in which the Council took place. The modernist crisis of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was suppressed with zeal by the Popes of the time, culminating in the Encyclical Pascendi Gregis of Pope St Pius X and the imposition of strict measures to prevent modernists from holding teaching positions in the Church. During the course of the twentieth century, various developments in Catholic studies came about. The study of the scriptures increasingly examined literary and historical questions; there was a movement back to the sources of tradition (ressourcement) with a renewed study of the Fathers of the Church. A key area of discussion was how Christian philosophy could develop in response to new discoveries in the natural sciences, especially concerning physics and its description of matter, and biology with its description of the evolution of living things. During the reign of Pope Pius XII, some theologians were censured for opinions contrary to the teaching of the Church, but the Pope himself, in his encyclical Humani Generis, recognised that there was room for the development of doctrine. Many theologians sought for a new synthesis of faith and reason which would pass muster in a world which had an immensely greater knowledge of the universe than was available to St Thomas Aquinas. The challenge was (and is) to establish the outline of such a synthesis without rejecting the perennial philosophy or the doctrine of the faith. (Taking up this challenge is this is the distinguishing characteristic of the Faith Movement to which I belong.{{2}}) On 28 October 1958, at the age of 77, Giuseppe Roncalli was elected Pope to succeed Pope Pius XII. He was expected to be a “caretaker pope”, to reign for just a few years and not do anything dramatic. He did only reign for four and a half years, but less than three months after he was elected, he announced his intention to convene a General Council of the Church. Famously, he said that it was time to open the windows of the Church and let in some fresh air. On Christmas Day, 1961, Pope John issued the Apostolic Constitution Humanae Salutis by which he formally convoked the Council. The constitution reflects in some sections the context to which we referred: the Pope said that there was a “crisis in society”, and that “Humanity is on the threshold of a new age.” Despite referring to material progress without a corresponding moral advance, he was optimistic, rejecting “distrustful souls” who saw nothing but darkness, calling for hope after the “successive bloody wars of our times.” With regard to the Church, Pope John was also upbeat. He said that the Church had not remained a spectator of events but had closely followed “the evolution of peoples, scientific progress, and social revolution.” Concerning the interior life of the church, he said:and lastly, from her own breast she draws the richest energies, for the sacred apostolate, for devotion, for encouraging the taking up of her action in all fields of human activity. This she does firstly in the work of the clergy, who with doctrine and virtue show themselves more and more ready to fulfil their responsibilities; then also in the work of lay people who are more greatly aware of the tasks entrusted to them in the Church and in a special way the office, by which each is bound, of zealously carrying out the work of assisting the ecclesiastical hierarchy.{{3}}This optimistic view of the Church’s life informed Pope John’s decision to call the Council. He contrasted “a world which displays a serious state of spiritual poverty and the Church of Christ, still so vibrant with vitality” and hoped that the Church would contribute to the solutions of the problems of the modern age. He set out his aim for the Council:

Therefore the forthcoming Ecumenical Synod is celebrated happily at a time when the Church burns with more generous zeal for strengthening her faith with new energy, and for sweetly refreshing herself with the glorious spectacle of her unity; at the same time she feels more earnestly that she is obliged by that responsibility not only that she might make her wholesome strength more effective and that she might promote the sanctity of her children, but also that she might bring forth an increase in the sharing of Christian truth and in the progress of her other practices.{{4}}Church Unity was one of the key desires of the Pope, though it is clear from his expression that this unity would not be a unity indifferent to doctrinal teaching. He said that at a time of efforts to bring about Christian unity, it was natural that the council should:

more richly show forth the heads of doctrine and should exhibit those examples of fraternal charity; with these set forth, Christians cut off from the Apostolic See might be kindled more keenly to that same unity, and that a road, as it were, should be strengthened for them to pursue it.I have quoted at length from this part of Humanae Salutis because there are a number of misconceptions about the calling of Vatican II. Pope John did not see the Council as a remedy for an ossified, rigid and moribund Church. On the contrary, he considered the Church full of vitality and able to make a contribution to solving the world’s problems. He did not see the laity as downtrodden and disempowered: again on the contrary he was aware of the great part that the laity were actively taking in the life of the Church. His idea in calling the Council was that a Church that was healthy and active (as we can see from the statistics of the time) would be given greater spur to even more effective action by the encouragement of a General Council.

At the beginning of the Council

In Humanae Salutis, Pope John spoke of a vast programme of work which was then being prepared. As he said:On that account questions are proposed regarding both the doctrine of the faith and the carrying on of life; and on that account they are proposed so that Christian teaching and precepts should be fitted to the varied reality of life and so that they should lead to the benefit of the mystical body of Christ and its sacred responsibility, which pertains to the supernatural order. These things certainly apply to the Divine Scripture, sacred Tradition, the sacraments and prayers of the church, the discipline of morals, the works by which charity is exercised and care is taken for those in need, the apostolate of the laity and missionary initiatives.{{5}}These matters all formed part of the various documents of the Council. Pope John also spoke of the temporal order, saying that the church wished to be Mater et Magistra (Mother and Teacher) because of her knowledge of that help and support which could make the life of individuals – all of whom are called to be saved – more human. He hoped that the Church would shed a Christian light on the problems facing the world. This concern was also addressed in the documents of the Council.

The beginning of the Council

The Council opened on 11 October 1962. Pope John continued to sound an optimistic, disagreeing with the prophets of doom, and rejoicing in the fact that the Council was able to meet without undue interference from the civil authorities. He said that the principal concern of the Council was the defence and advancement of truth:The greatest concern of the Ecumenical Council is this: that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be guarded and taught more efficaciously.{{6}}Emphasising the importance of doctrine, Pope John said:

the Twenty-first Ecumenical Council, which will draw upon the effective and important wealth of juridical, liturgical, apostolic, and administrative experiences, wishes to transmit the doctrine, pure and integral, without any attenuation or distortion, which throughout twenty centuries, notwithstanding difficulties and contrasts, has become the common patrimony of men. It is a patrimony not well received by all, but always a rich treasure available to men of good will.{{7}}Pope John went on to make a statement which has often been distorted:

The deposit of Faith is one thing, or the truths that our venerable doctrine contains; the way that they are expressed, though with the same meaning and the same way of thinking (eodem tamen sensu eademque sententia) is another thing.{{8}}With regard to the repression of errors, Pope John said that nowadays the Spouse of Christ preferred to use the medicine of mercy rather than severity, because the errors of our time are so obviously against the truth that men are inclined to condemn them without the Church’s help. Again with great optimism, he hoped that the Church could raise up the torch of religious truth to show men their true dignity so that they would be drawn to the Church as the means of salvation. He also spoke of the promotion of the unity both of Christendom and of the whole human family. Fifty years on, with the benefit of hindsight, and with sadness, we must admit that Blessed Pope John’s optimism has not been fulfilled. Doctrinal errors abounded much more within the Church after the Council than before, and the human family, at least in the West, rather than being drawn to the great light of truth shown by the Church, has legalised abortion and experiments on embryos, and increasingly encroaches on the rights of the Church. Indeed the human family in many countries is now proceeding rapidly to the redefinition of the family by legalising same-sex “marriage.” The first meeting of the Council was intended to elect the members of the ten commissions for the council that would direct much of its work. While Cardinal Felici, the Secretary General of the Council was explaining the election procedure, Cardinal Lienart, one of the ten Council Presidents, rose indicating that he wanted to speak. He proposed that the Fathers should have more time to study the lists so that they could choose the members of the Commissions. Cardinal Frings seconded, the proposal was greeted with applause and Cardinal Felici closed the first meeting of the Council after only fifty minutes. The Bishops of Germany, Austria and France, together with those of Holland, Belgium and Switzerland worked together to provide a list of candidates which was less dominated by the Roman Curia and more international – though in the event the African Bishops felt that they had been under-represented. This was the first “victory” of what came to be known as the “Rhine Group” of Bishops. The idea of the preparatory work undertaken over three years in preparation for the Council, was to provide the schemas for discussion. The idea was that these would be examined and discussed, then accepted, amended or rejected. Pope John said of these schemas that had been painstakingly prepared:

Filled with great joy, we inform you that these eagerly intense studies, are now nearing completion, studies in which the Purpled Fathers,{{9}} Bishops, Prelates, Theologians, labourers in canon law, knowledgeable and expert men have produced a glorious and co-operative work.{{10}}Notwithstanding the eulogy of Pope John for the work of the Purpled Fathers and others, it was all thrown out a few weeks after the beginning of the Council. The five schemas had been sent round to all the Bishops prior to the Council. The theologian Edward Schillebeeckx wrote a commentary on them which was distributed widely. He praised the fifth, on the Sacred Liturgy, but heavily criticised the other four. Following the distribution of his commentary, the Fathers voted to consider the schema on the Sacred Liturgy first of all. In fact, Cardinal Frings proposed substantial changes even to this schema, including some major changes to the Liturgy. Cardinal Ottaviani who opposed these changes, spoke for his allotted fifteen minutes and was then peremptorily cut off when Cardinal Alfrink turned off the microphone. This was widely seen as a welcome humiliation of a senior Curial Cardinal. The Council was adjourned on 8 December 1962 and was due to begin again the following autumn. On 3 June 1963 Blessed John XIII died. That could have been the end of the Council since any Council is immediately suspended when the Pope dies. However, Pope Paul VI was elected on 21 June 1963 and immediately announced his intention to continue the Council. Therefore the preparatory work for the next session could continue after a brief interruption.

The progress of the Council

It could be said that Pope Paul VI, who had, of course, been participating in the Council already as a Cardinal, recognised the de facto direction that the Council was taking and put this into due order. He reaffirmed the aims of Pope John but clarified them and made them more specific. He stressed that the Council was a pastoral council, emphasised the desire for unity and for dialogue with the world, and the need for renewal within the Church. One of the most important themes was the Council’s aim of looking at the nature of the Church and the role of the Bishop. During this part of the Council, the Fathers and the Pope formally approved the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy and the Decree on the Means of Social Communications. On 8 November, there was a dramatic exchange on the Council floor: Cardinal Frings heavily criticised the Holy Office and its methods. Cardinal Ottaviani, the Secretary of the Holy Office (in those days, the Pope was considered the head of this dicastery) replied with a passionate defence of the Holy Office. It is a notable historic irony that the expert theologian (peritus) who was advising Cardinal Frings at this time was the young Father Joseph Ratzinger who himself later became the Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, as the Holy Office was known after its reorganisation. The most important event of the sessions of the Council held in the autumn of 1964 was the promulgation of the Constitution on the Church which was perhaps the most fundamental of the Council’s documents. The documents on Ecumenism and the Eastern Churches were also finalised. By this time, the effects of the Council were beginning to be felt in the Church as a whole. Following a Motu Proprio of Pope Paul VI, much of the Mass was being said in the vernacular in many places, and other liturgical changes were beginning. At the same time, Pope Paul VI was acutely aware of what he called a “tidal wave of change” which was affecting the Church. Speaking of this in his first Encyclical Letter, he said:It drives many people to adopt the most outlandish views. They imagine that the Church should abdicate its proper role, and adopt an entirely new and unprecedented mode of existence. Modernism might be cited as an example. This is an error which is still making its appearance under various new guises, wholly inconsistent with any genuine religious expression. It is surely an attempt on the part of secular philosophies and secular trends to vitiate the true teaching and discipline of the Church of Christ.{{11}}He also spoke of the importance of obedience as opposed to a “a spirit of independence, bitter criticism, defiance, and arrogance.” For many Catholics there was a growing realisation that many things that had been thought permanent were now up for discussion. One significant example in the lives of Catholics was that the Eucharistic fast was reduced to one hour. On a different note, it was on the close of this part of the council, on 21 November 1964 that Pope Paul formally honoured the Blessed Virgin Mary with the title “Mother of the Church” though this papal act was also the source of some controversy. One of the actions of Pope Paul VI in the preparatory period before the sessions of 1964 was to end the requirement of secrecy at the general sessions of the Council. In fact, the press had already managed to gain interviews with Bishops who were present at the Council and were heavily influencing public perception of what was happening. This was a consequence of the growth of the modern media. Inevitably also, it meant that those most skilled at dealing with the media were able to exercise an influence on how the Council and its debates were presented to the world. Many had not yet begun to realise the importance of this strategy. The last period of the Council in autumn 1965 saw the completion of the remaining documents. The most important was the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World which addressed one of the key themes of both Pope John and Pope Paul, as well as inviting Catholics to consider the problem mentioned earlier of the question of science and religion, reason and faith. When people speak of Gaudium et Spes, they rarely mention this crucial aspect of the document. This session approved two of the more controversial documents: the Declaration on Religious Freedom and the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions. In the third paper, we will look at why these were controversial and the state of the question today.

Our task in the Year of Faith

In this brief overview of the history, context and progress of the Council, we can barely touch the surface of an event that has had profound repercussions in the Church and in the world. It is important also to consider by way of conclusion the task that we have during this Year of Faith when we look at the Council fifty years on. A reference to the Gospel used by Pope John and often spoken of in reference to the Council is that we should “read the signs of the times.” In the 1960s, it was possible to express optimism about the reconstruction and renewal that was going on in the world after the second world war. “Modern” was used invariably as a complimentary expression. The Church wanted to appeal to modern man, to be modern and to embrace modernity. Now, fifty years on, what is modern is very different. It is possible for us to learn from the experience of the praise of modernity and to place it in the context of the Church’s constant tradition. Re-reading the Council texts and the addresses of Pope John and Pope Paul, we can be aware, as many were not aware at the time, of the warnings and qualifications that they included, of their emphasis on the doctrinal teaching of the Church, and of their assumption that the truth would be its own defence. In a world that has moved on in ways that Pope John and Pope Paul would not have imagined in their worst nightmares in terms of the loss of faith among Catholics, the growth of dissent within the Church, liturgical abuses, the breakdown of the family, widespread cohabitation, abortion, embryo experimentation, same-sex marriage, and, what would have been unthinkable so close to the second world war, the beginning of a new movement for euthanasia, we must also read the signs of the times. The purpose of this Year of Faith is to renew our faith as individuals and as members of the body of Christ. Further study of the documents of the Council is always worthwhile. A pressing need is for accurate English translations to be made, since those currently available are untrustworthy. As priests, we also need to renew our knowledge of that Catholic theology which Pope John, Pope Paul and the Council took for granted. In the years since the Council, the formation of many priests has been lacking in the solid and systematic grounding that was provided by the much-derided manuals. Things are getting better in many seminaries now, but there is a generation of priests who did not receive a solid theological formation. It is up to us to make up that lack. On that foundation, we can understand better what the Council was getting at. Most of all, we must love the Church as our Mother and Teacher to use the phrase so beloved of Pope John. “The Church is alive, the Church is young” said Pope Benedict, quoting Blessed Pope John Paul in his inaugural sermon. The Church has been through many vicissitudes in its history but Christ has never failed in his promise: “I am with you always, yes to the consummation of the age.” (Matt 28.20) [[1]]Ratzinger, J. Principles of Catholic Theology, p. 378.[[1]] [[2]]There is further information at www.faith.org.uk.[[2]] [[3]]Bl Pope John XXIII, Apostolic Constitution Humanae Salutis. 25 December 1961 n.5. Oddly (though this is not a unique instance of inconsistency) the Vatican website has the text of this Constitution in Latin, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish, with no official English translation. There is a translation on the internet but I have found it seriously defective and misleading; therefore I have translated the quotations myself from the Latin original text.[[3]] [[4]]Humanae Salutis n. 7.[[4]] [[5]]Humanae Salutis n. 10.[[5]] [[6]]Bl Pope John XXIII. Allocution at the Solemn Opening of the second Vatican Council, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. 11 October 1962. n. 5.[[6]] [[7]]Gaudet Mater Ecclesia n. 6.[[7]] [[8]]Ibid.[[8]] [[9]]The expression is “Purpurati Patres”, a traditional Roman expression referring to Cardinals.[[9]] [[10]]Humanae Salutis n. 16.[[10]] [[11]]Pope Paul VI, Ecclesiam Suam. n. 26.[[11]]