Homily at St Patrick’s, Colebrook, Tasmania

The London Tablet of 2nd September 1848 published a long letter under the name of A. W. Pugin, Esquire. At a time when his views were being opposed by churchmen in high places, Pugin makes a sustained and eloquent argument for the restoration of true Catholic architecture.

He has in his sights what he denigrates as the cold paganism of the Classic style, decrying, in one of his colourful turns of phrase, the “adaptation of heathen temples by infidel architects.”? “Revive true Catholic faith and devotion …” writes Pugin,

… restore the old reverence, and gladly will men welcome old things — arch and aisle and pillar, and chancel, and screen, and worship as their fathers worshipped — the hour is coming and now is, when the old glory of the sanctuary will be restored, and solemnity revived with returning faith … pillar and pinnacle and cross-crowned spires will rise toward heaven, the sign of the resurrection of the body and life everlasting.

As evidence of the revival gaining pace, and not only in the old world, one can sense the delight with which Pugin records that

more than one bishop has departed across the ocean to the antipodes, carrying the seeds of Christian design to grow and flourish in the new world and soon the solemn chancels and cross-crowned spires will arise on the shores of the Pacific …

Of these prelates, we may suppose that uppermost in Pugin’s mind might have been the first Bishop of Hobart Town, Robert William Willson. When the bishop arrived here in his new diocese aboard the Bella Marina in 1844, her holds contained among those ‘seeds of Christian design’? a scale model of what would one day be realised as this church. So today we worship at an altar in one such ‘solemn chancel,’? raised on this country hillside in the antipodes over one hundred and fifty years ago, and now so beautifully and generously restored.

In this place, with arch and aisle and pillar and screen, we commemorate the birth of its architect in liturgy and music, in solemn rite and sacrament. In the unity of faith and continuity of Catholic worship, if Pugin were to find himself kneeling with us at this altar we may imagine him entirely at home, the lapse of time between his place and time and ours dissolved in an instant recognition of this scene, and absorption within the action in which we are at present engaged.

Within his brief life of forty years — a brilliant burst of extraordinary energy — it was said of Augustus Welby Pugin that he achieved more than most men manage if they survive to be a hundred. And not only as a prolific artist in many forms, but in a rich variety of human activity and relationships, by no means least as a husband and father.

Pugin first married at 19 years of age, only to be widowed a year later when his wife Ann died in childbirth. He married a second time: with Louisa he had six children, two of whom were to succeed their father as architects. After twelve years of marriage Louisa died. Finally, for the last four years of his own life he was married to Jane, by whom he had two further children.

From their home that came to be established at Ramsgate overlooking the sea there went out a charity and a generosity that embraced the poor and unemployed, that was shown to sailors rescued from ships in distress, that provided without question for those who were in need, even creating employment for them. There was an ideal at work, profoundly Christian, against the often stark and ugly social background of the early Victorian age, a belief that the greatest privilege given to man in this life is to offer his very best in every endeavour for the highest of motives, the glory of God. This ideal, proceeding from faith, is the key to understanding not only Pugin the architect, but Pugin the man.

When at the age of 23 Pugin embraced the Catholic faith, he did so with a passion that was lifelong and penetrated into every corner of his life. He entered the Catholic Church in England only five years after she had been emancipated from the last of the penal laws, and was beginning to emerge into her second spring after a bitter winter of persecution.

Pugin was among those who found the ideal of the second spring in a continuity with the glorious summer of the high Middle Ages. Three centuries earlier, the English Church of a thousand years flowered with the beauty of her architecture, music, and liturgy, perfected in the great cathedrals and abbeys, emulated with rustic charm in simple village churches, united as one with the universal Church in a fervent communion with the See of Peter. Within two generations all this was swept away.

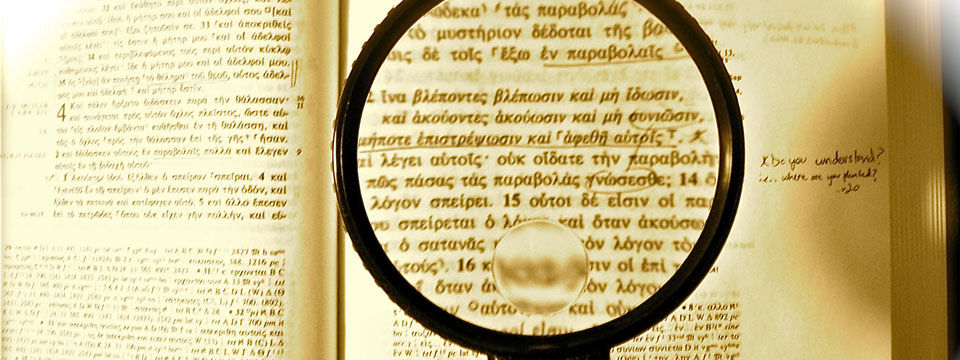

The architecture of the ages of faith certainly influenced Pugin?s conversion. For the rest of his life it was for him the inseparable witness to the truth of the faith itself. “Applying myself to liturgical knowledge,” he wrote soon after, “what a new field was open to me! And with what delight did I grace the fitness of each portion of those glorious edifices to the rites for whose celebration they had been erected.”

Order, beauty, perfection, the witness to truth. In his own time, Pugin is one of those God- possessed individuals who threw all the energies of his life at the task of making the divine present, to be grasped and loved, within the disordered, ugly, tragically imperfect and wayward world of human affairs and conduct. He did it through architecture and design according to what he saw as the best model and truest principles available in his time and place. He did it in his personal life of devotion, of charity and social activism. It is through Christ, His Church, and the Christian culture flowing from the incarnation and redemption, that man and his world here below can be prepared for its sublime destiny, a destiny which, in Pugin’s vision could be at least glimpsed through the order and beauty of the Gothic form.

From time immemorial, on this Second Sunday of Lent, the Church has proclaimed the Gospel of the Lord’s Transfiguration. The transfiguration is a unique moment of revelation. Those who are to witness it are chosen, and taken aside. “Jesus took with him Peter and James, and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain by themselves.”? It is a moment of metamorphosis, a moment of transcendence. In dazzling luminescence the eternal glory of the Son of God is manifest, dispelling the shadows of this world. Heaven opens, the cloud is pierced, the voice of the Father, the Almighty, the uncreated, is heard in the words of earth: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.”

In fear, in awe, in adoration, Peter, James and John fall prostrate, their faces to the ground, as if the entire creation from the first moment of time is gathered in an adoration transcending time. Six days we are told have passed: this is like the seventh when God rested, when all creation was complete.

In Rome long ago St Leo the Great told his people that all that was visible in Christ had passed over into the sacraments. He was saying that for ever in the Church, through the material and visible forms and signs employed in her liturgy, the fullness of divinity will continue to splendour forth from heaven into a creation still groaning in travail. In the Church, in sacramental signs until time is no more, the Lord of glory will remain present to sustain, and to comfort and lead His People on their journey home, to reach a final transfiguration in the resurrection of the body.

For us today commemorating Pugin’s life and its legacy, we can learn much from his evident desire to give glory to God, simply to respond to His divine transcendence, His goodness, His beauty, and His truth. Nothing less than the best and most beautiful, the most befitting to the divine glory, can be worthy to be offered. This embraces everything, from the setting of worship itself, to the decorative form and engraving of the sacred vessels, to the smallest detail of decoration on vestment and altar linen.

After the turmoil and upheaval of the past fifty years in western thinking and social values and consequently within the Church, how do we regain the sense that it is God Himself who is the object of our worship, our love centred on Him and not upon ourselves? How do we escape from spiritualities focused inwardly upon community and devised, one cannot but think, simply to make us feel good about ourselves? How can we worship in such a way that a liturgy of transcendence urges us also to cry out, “Lord, it is good for us to be here”? Pugin lamented in his own day “the corrupt and artificial state of ecclesiastical music”. As we are uplifted by the transcendence of the sacred chant and polyphony offered to God with beauty and grace in this Mass, how are we to engage in lifting the present state of music in our churches from what seems to be a perennial predicament?

Pugin observed that “England can never be Catholicized … by the conversion of the liturgy into a song-book, and the erection of churches whose appearance is something between a dancing room and a mechanics?institute.”?“This country”, he wrote, “will again receive Catholic truth in all its fullness by our rising to the high standard of ancient excellence and solemnity, and not by lowering the externals of religion to the worldly spirit of this degenerate age.”

On the mount of the Transfiguration, Christ our Lord took his disciples out of the world of the mundane into the world in which all is made new, the world in which humanity is perfected in divinity. What draws us to commemorate Pugin’s Bi-centenary must surely be this: like all the great artists of the Christian tradition, he by his art has made even more luminous for us, for the Church, that path of beauty in her worship that raises her children above the mundane, to glimpse the glory of the world to come, and to enjoy even now, a foretaste of its joys.